Slim was a man of around forty who I knew forty years ago when I lived up on the coast of Maine. He was skinny but strong; wore unfashionable glasses with thick, brown rims; had light brown hair graying at his temples, greased back like Elvis; chain-smoked; had a leathery, tanned face; and had the sort of pointed jaw, missing mass in the cheeks, that made me wonder if he had any molars left to pull, though it was hard to tell, for he hardly ever opened his mouth. I hung on his every word, which was easy to do, for he rarely spoke any. I know he had some coffee-stained front teeth, for he occasionally would grin helplessly, despite his shyness. Usually he was smiling due to the palaver of a fellow he worked with named Tubs, who was Slim’s opposite: Short, round, balding, jolly and very talkative. The two men seemingly had only one thing in common: They were hard workers, able to take on a wide variety of jobs and complete them with speed and skill.

I think I first saw the two men working in 1974. It was a simple job, delivering my mother a pick-up truck load of firewood. I admired the speed of their unloading. It took less than five minutes. Slim never touched the logs, because he used a couple of small hooks with wooden handles, specialized tools I have never seen anyone own or use since.

The two men worked like it was some sort of race, with the musically clopping logs flowing off the tailgate of the truck like water. They never needed to stop for a break because they completed the job so swiftly, nor did they grunt and grimace as if it was some big effort. As they worked Tubs was telling some story and Slim was nodding and smiling. Then they saw me watching and immediately became suspicious.

This was to be expected. In 1974 the Vietnam War wasn’t over, and I had long hair. Slim had seen action serving in Korea, some twenty years earlier. In fact some of his shyness may have been due to post-traumatic stress. I imagined my long hair automatically made me be an unpatriotic draft-dodger in his eyes, which made communication between us difficult.

The irony of the situation was that I was not what my long-hair suggested; I had unexpectedly broken my connection with the so-called “counter culture”, and perhaps was in some ways more conservative than Slim, and certainly more conservative than Tubs.

I had not intended to become conservative. I had started out by doing the expected and the acceptable (to hippies) things hippies did: Hitchhiking long distances; joining some loose confederations and cults called “communes”; becoming involved in (and eventually repulsed by) unsavory adventures involving sex and drugs; and, as a sort of conclusion, traveling to India to seek “enlightenment”. (The “Beatles” did it, Peter Townsend of the “Who” did it, and Melanie Safka did it when she was disillusioned).

To be blunt, “enlightenment”, as I then envisioned it, was a sort of Disney-world hallucination lacking the harshness and schizophrenia of LSD’s. I had somewhat vague hopes that some door would open in my forehead, and I would be swept into an experience of shimmering colors and lights, resulting in bliss. Others claimed they’d had such experiences. I hadn’t, and to be honest I really was uncertain where I was going or what I was after, as I headed to India. All I was really sure of was that I didn’t want to work a Real Job.

Instead of visions, or a meeting with any sort of con-artist-guru who promised such things, I had the good fortune to blunder into somewhat boring “good advice”, from the disciples of Meher Baba. (Meher Baba stated he was the Avatar.) Largely the advise they gave was not the sort that would get me out of working a Real Job, so I was not all that gratified.

For example, they stated I should not neglect “attending to my worldly responsibilities,” which initially sounded OK, because I felt a poet’s “responsibility” was to nibble an eraser, gaze dreamily at the sky, and avoid getting a Real Job. Then they seemed to suggest such behavior was deemed “responsible” only if God permitted such behavior to pay my bills, (via hard work, and also fate or “karma”). This amendment soured me slightly, though I kept my opinions to myself. Yet their advise was delivered in such a lovingly down-to-earth manner that I found myself not caring all that much about the subjects we discussed, and instead admiring their down-to-earth delivery. I started to think being down-to-earth might actually be a good thing, and not necessarily be unimaginative “conformity” and a sign I was a “square”.

I must have been a very odd American for the disciples of Meher Baba to have to deal with. Here I had traveled half-way around the world, yet I asked no questions. Somehow I felt asking questions was disrespectful. So I just observed, and kept my questions to myself. I was scheduled to visit for two weeks, but my TWA ticket allowed me to delay my departure, so I kept delaying, and observing. After nearly three months I headed home, because I knew my family and especially my mother would be upset if I skipped Christmas. Also I was flat broke and had run out of people to borrow from. Now I look back and want to slap my forehead, because I asked so few questions, but at the time it was just the way I was, namely a three-letter word: “Shy”.

Because I never asked for advice I can’t say I ever received any, per se. Perhaps I did hear others ask questions I felt were rude to ask, and listened intently to the answers they received. But largely the “advice” I received was contained in the “example” Meher Baba’s disciples set.

I think what impressed me most was that the followers of Meher Baba were not “groupies”, like hippies tended to be. Perhaps hippies were dead set against wearing uniforms, but they tended to be copy-cats and “uniform” in other ways. For example the “Dead-heads” (fans of the rock-group “The Grateful Dead”) agreed about certain things, and if you veered from their “norm” they could be disagreeable. They tended to be birds of a feather who flocked together. The disciples of Meher Baba, on the other hand, were strikingly individualistic, definitely not birds-of-a-feather. They were as different as different could be, yet strangely not in conflict. How was this possible?

That was the question I should have asked, but was too shy to ask. It was on my mind because I had witnessed hippy communes, made up of very similar and on-the-same-page people, disintegrate over minuscule differences tantamount to straws that could not even break a field mouse’s back, let alone a camel’s. How could Meher Baba’s disciples manage what hippies could not? But I never asked, and instead observed.

Meher Baba himself had died nearly five years earlier, on January 31, 1969, yet it was obvious his influence was still profound. However I was not satisfied with “influence” alone. I didn’t want to only see the sunburned people after the Sun had set. I wanted to see the Sun. I suppose I was like Doubting Thomas, refusing to believe in Christ until he himself could finger the wounds on a risen Christ’s hands.

I was not gifted with Thomas’s experiences, and it was frustrating to me, for I constantly met people who had experienced a “risen” Meher Baba.

There was some event called “The Last Darshan” that Meher Baba had been planning-for, scheduled between April and June, 1969, which you might think would have been cancelled when he inconveniently died in January. But people went ahead and the event was held, and the people (from all over the world) who attended the event stated Meher Baba was present in spirit, and that all sorts of amazing stuff happened. However I was not informed and did not attend and wasn’t a witness. I was not gifted with such grand experiences.

In some ways I am like the dour man from Missouri who always says, “Prove it”. I demand certainty. Even back at age twenty-one I had too often been played for the fool, too often been the laughable sucker and embarrassing chump, and I’d be damned if I’d allow it to happen to me again. But I received no countering certainty or “proof”, in terms of supernatural events.

This is not to say I didn’t own a private, secret, inner world, nor didn’t have intimate, muttered conversations with God. I just didn’t hear answers delivered in a booming baritone. My personal “miracles” tended to be coincidences, such as a butterfly landing on my nose, or a certain song coming on the radio, which couldn’t withstand determined cynicism. My “visions” were dismissable as being the result of an overly active imagination; the same psychologists who were amazed at my ability to “free-associate” completely shredded any hopes I might have that my fantasized images might mean something positive. They subjected my poetry to a sort of ruthless cross-examination, hyper-analyzing every symbol, supposedly to increase my self-awareness, but in fact increasing my doubtfulness. In the long run the awareness I developed was that I should keep such thoughts to myself. Rather than making me more outgoing psychology hardened my fortress of shyness.

All the same, hanging around Meher Baba’s disciples was a deeply moving experience. Perhaps people-who-were-highly-individualistic-and-different-yet-who-managed-to-lovingly-get-along struck me as a bit “supernatural”, in its own right. After all, my own parents were brilliant, charming, and in some ways very similar people, but got a divorce. And the political “hawks” and “doves” of the USA were not getting along, and the so-called “alternative” hippy lifestyles were crashing and burning everywhere I looked. Meher Baba’s disciples were different. I saw, in these kindly and generous foreigners, an example I desired to follow, and people I wished to emulate, though I was highly individualistic in my own right, and couldn’t see how I could be a true “follower” of Meher Baba. One might say I was attracted, and perhaps a “follower-from-a-safe-distance”.

Oddest was the lack of “rules” they gave me to follow. The “good advice” lacked all the commandments which many scriptures make into an elaborate and detailed system of “laws”. In some ways I found this disturbing, for in some ways I was aware that the most productive times of my life had involved some sort of brutal drill sergeant demanding discipline and laying-down-the-law, whether the “drill sergeant” was a strict school’s headmaster, or an inanimate and savage storm at sea.

For the most part Meher Baba seemed to forego issuing commandments, and instead to merely describe the problems inherent within addiction-to-creation, and describe the benefits of escaping creation into the embrace of the Creator, without (in my view) mapping out what rules and laws one should obey during the transition. But I did gather, without asking any questions, two things which might be called “laws”, although they were “good advice.”

I should not take drugs and should not indulge in promiscuous sex.

Absorbing this good advice, and accepting it, put me at odds with my hippy peers. Though I was dreaming about harmony, I was plunged into opposition.

When I returned to the United States I discovered I didn’t fit in where I had once fit in. I wanted to share what I had glimpsed to the cult-like groups I was associated with, but seemed unable to find the right words. I didn’t want to reject anyone, but was inarticulate, and felt I had a very slow mouth among very fast talkers. After experiencing ridicule for suggesting sober, prudish, down-to-earth behavior might be wise, I felt hurt, rejected by my peers, and gradually began to search for a different society, where I might fit in.

Looking back, it seems it would have been for the best if I had made the separations swift and dramatic, and as complete as the separation between civilian life and boot-camp. But I was not a quitter, and always held out hope for improvement in relationships that, in truth, were withering away. Unfortunately this meant that, rather than removing a forearm-band-aid swiftly, I made it a long, slow, painful, hair-plucking, and drawn-out process.

To me it seemed loyal and faithful to give people who had in some way betrayed me a second and third chance to betray me. I prolonged my misery, for I felt forgiveness was spiritual, and was confused about when one should “shake the dust from your heels” and leave people in the past. I felt I should forgive people “seven-times-seventy times”, and consequently handed “my pearls to swine”. Last but not least, I was in some ways atrociously arrogant, and it was inconceivable to me that others wouldn’t realize how marvelous I (or at least my poetry) was, understand the enormous error of their ways, and profusely apologize. I felt that, if I only was forgiving long enough, they would mend their ways. “Someday they’ll be sorry.”

It didn’t happen, but I am getting ahead of myself. At age twenty-one I was still full of optimism, and assumed I was moving to Maine only for a brief time. I felt I needed to retreat and regroup, and “get my head on straight,” but imagined that soon my self-imposed isolation would resolve into happy reconciliations and reunions, and the “communes” would become new-and-improved, and we would all stride forward together into the bright uplands of happy-ever-after. (My prediction was that world-wide crises would come to a climax in five or six years, around 1980, and happy-ever-after would happen soon afterwards.)

In some ways I was expectantly waiting for cold stones to get up and warmly dance around singing, and such situations are bound to become frustrating, as you wait, and wait, and wait. Worst is the simple fact that patience of this sort doesn’t pay a positive dividend, but rather one starts to see a sort of rot set in. “All things come to they who wait”, but the best lumber turns into punk if it sits unused. It is through action that spiritual truths are revealed. I was just beginning the process of learning this Truth the hard way, when I moved to Maine.

In conclusion, I was not the typical “long-hair” Slim and Tubs thought I was. I was an ex-hippy with a newfound respect for the down-to-earth, and Slim and Tubs were the very sort of down-to-earth people I respected, but they felt zero affinity towards the likes of me.

Actually an odd affinity did exist, because Slim and I were both very shy, though I suppose Slim would have been horrified (and perhaps even insulted) if anyone suggested there was any sort of similarity between the two of us. He had worked and paid his way since he was sixteen, whereas I mooched off my mother.

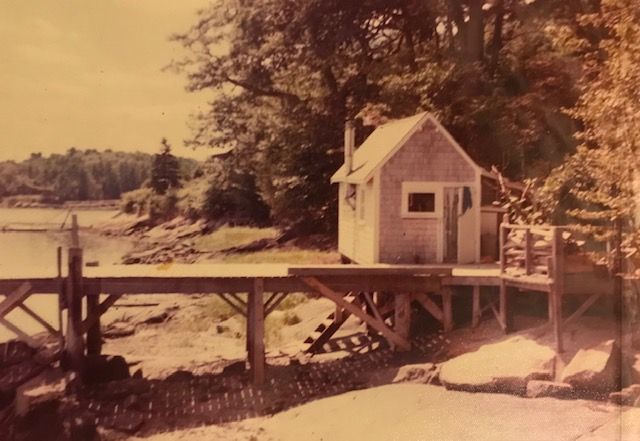

I didn’t actually live in my mother’s basement. My step-father had bought a lovely piece of property overlooking the ocean to retire upon, which had two smaller cottages a short ways down a steep hill from the main house, and then, down an even steeper embankment, a dock, and on the dock was a shack. The moment I laid eyes on the shack I felt it was perfect for a poet. It was a lovely abode, (when the weather was warm), but in the eyes of Slim and Tubs living there merely made me a shiftless layabout mooching off his mother.

I tended to sleep late, because I usually had stayed up late the night before writing. I had strong legs and good lungs, and, clutching a tall, oversized, bright-orange coffee cup, would sprint up the staircase from the dock and jog up a steep drive to my mother’s house, to take advantage of the fact her kitchen had an extra faucet that delivered boiling water. This skipped the bother of waiting for water to boil in my shack (which did have electricity.) I’d stir instant coffee and four spoons of sugar and cream into my oversized cup, and often was back down in the shack at my typewriter within minutes. I’d guzzle the coffee, and often sprint back up to my mother’s house only an hour later.

Because I was so addicted to caffeine, my visits were frequent, and from time to time I’d barge into my mother’s kitchen as she had coffee with various people. (The kitchen opened into a dining-room with a beautiful view.) On such occasions I felt it was rude not to pause briefly and pretend to be sociable for at least as long as it took to smoke a cigarette. (Smoking inside was commonplace back then.) Once in a while the persons my mother was having coffee with were Slim and Tubs.

Some women of wealth have an egalitarian streak, or perhaps a mere curiosity, which has them inviting the hired help into elegant dining rooms and serving them coffee from expensive china. I have often been flattered by such generosity, in my own time as a gardener and handyman, and have always tried to reciprocate by being polite, (and as witty and charming as I dare), and asking questions and nodding at the replies. Back in 1974 I knew far less about being “hired help”, and was fascinated by Slim and Tubs holding coffee cups with their pinkies raised, and chatting comfortably with my mother.

My mother was amazing when it came to making people comfortable, which at times made me uncomfortable. Certain aspects of her hospitality didn’t seem entirely honest. For example, she spoke with an elegant English accent, when in fact she was a poor girl who had grown up in a broken home in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. A few times when, as a teenager, I had pushed my luck with the good woman, I had heard that English accent completely vanish, and in surprise had backed away from a fierce Fitchburg wench whom no gentle poet would ever want to mess with.

Despite the fact I was aware there was a side of my mother she did not expose to the general public, I clung to the incongruous and childish belief she was innocent and saintly. For example, I assumed hippies knew more about sex, although my mother had given birth to six children. For another example, I felt hippies were more “experienced” because they had taken LSD, although hippies had amnesia about what they glimpsed when drugged, while my mother remembered with vivid clarity, and had 29 more actual years of actual experience than I had. There is something audaciously comical about youth deeming their elders naive, but I felt my mother was naive and needed my protection.

Not that I had a clue of the wheeling and dealing that was occurring beneath the polite chit-chat, as my mother had coffee with Slim and Tubs. The two men were to some degree on the lookout for a rich lady who would supply them with their next paycheck, and she was on the lookout for local, Maine-Yankee carpenters who could do good work for a tenth of what an interior designer from Boston would charge. I had no idea such skullduggery was involved. I assumed they were above-board and up-front. To be honest, I was incapable of protecting my mother from tricky salesmen, and equally incapable of protecting Slim and Tubs from tricky Moms, because I myself was living in the clouds of idealism.

One cold,January morning in 1975 I came bopping into her kitchen, rumpled and yawning, with my tall, orange cup, and discovered them deeply involved in a discussion about maple wood. The low winter sun was flashing through winter clouds, slanting in through a window that showed a beautiful view of a harbor.

They didn’t look out the window, for the view was old to them, and instead they sat midst sunlit blue curls and wisps of cigarette smoke, intently discussing kitchen counters.

I quickly determined my mother didn’t like the orange Formica counters on the island between the kitchen and dining room, and wanted to replace them with maple. She didn’t want straight-grained maple, neither the creamy sapwood nor the buttery heartwood, and desired a grain less uniform, with “character.” Therefore they were discussing the prices of bird’s-eye, burl, and fiddle-back maple boards, all of which were expensive and made my mother look very disappointed and vaguely critical. As they spoke Tubs did most of the talking, sitting back and expansively ruminating with a jovial and optimistic expression, deferring to Slim when my mother wanted prices. Slim sat hunched forward with his hands folded as if he was praying, for the most part nervously smiling and nodding as Tubs spoke, but occasionally barking the prices of maple boards of various types in an authoritative way, at which point my mother would scratch out calculations on a yellow, legal notebook on the dining-room table, coming up with answers that she looked at with disapproval. Then they apparently arrived at some sort of insurmountable quandary, at which point Tubs sat even further back, locked his fingers behind his neck as a pillow, and looked out the window with deep seriousness, his face unusually grave, as if determining the fate of nations. Then his face lit up and he turned towards my mother with an unspoken idea. At the same point Slim winced slightly, and shrunk down a half inch, as if silently willing Tubs to keep his big mouth shut, but Tubs spoke.

Apparently there was a sort of sugar-maple lumber which not many people knew about. It came from a maple tree near the end of its life, when the growth rings became skinny but before the rot set in and the wood became punky in places, and therefore became unusable. Slim had a word for it. (I want to say “checkered maple”, but search-engines produce no such word.) It was typically light yellow maple wood, but had dark, broad veins of deep brown and even black running through it. When a sawmill sliced up a maple log which produced such boards they tended to cast them aside as relatively worthless, though the planks were solid. Tubs knew where he could get such boards for next to nothing. He wondered if he could bring some boards by, for my mother to look at, to see what she thought of the unusual coloring.

My mother looked intrigued. She always liked being unique, and I could tell she liked the concept of having kitchen counters unlike anyone else’s. She also liked the price. She looked out the window thoughtfully. Tubs smiled serenely. Slim chewed his fingernails as if the suspense was killing him. Then my mother turned to Tubs and said she was very interested in seeing what such maple boards looked like. Tubs nodded and smilingly said he’d bring some boards by. Slim sagged from stiff tension to palatable relief. Then the topic turned to the molding up where the wall met the ceiling, and I headed back down to the shack with my coffee, toying with a poetic idea involving maple planks, which I thought I might insert into a long poem I was laboring on.

The year was not 1829, and I was no Alfred Tennyson. There was absolutely zero market for long poems in 1975, but I thought I could create one. I fostered this illusion because my hippy friends spent hours listening to record albums (video games hadn’t been invented). We would sit and listen to a just-released album together, and have long discussions about what the songs meant. Sometimes, rather than spending an hour listening to an album, I would read them a long poem. (As I recall such readings came about due to a particularly enthusiastic friend demanding I do it, and had nothing to do with me overcoming my shyness and “selling myself”.)

What then happened was extremely gratifying, for, rather than appearing bored stiff or stampeding to the door, people would listen with wide-eyed, rapt attention, laughing at all the right places and growing misty-eyed when I became maudlin. They urged me to write more, looked respectful and interested while I wrote, gathered around to listen when I announced I was done, and never once told me I should get a Real Job. Then, in India, I had written a long story-poem in a wonderfully inspired fit, and it was well-received among total strangers when I read it to them. Due to this encouragement I had the idea I could sell my long poems, if not as printed pages, then as record albums (because people liked the sound of my reading voice.)

But by retreating to Maine I had cut myself off from such encouragement, and I found myself fighting “writer’s block”. I didn’t like admitting I needed encouragement, seeing such a desire as a weakness, as being susceptible-to and swayed-by flattery, but it was obvious that I craved attention. Isolation left me feeling marginalized, ostracized because I had changed my attitude towards sex and drugs, and a sense of profound loneliness descended and began staining my inspiration with gray.

I fought this bleakness with all my might, for most of my poems were in one way or another about how life is brimming with beauty, and I intended them all to be pep-talks for the disillusioned. For example, I might write about a person depressed because their garden was full of weeds, and then describe a friend showing up and weeding with them, turning the dreary task into a rapture about botany, and bugs, and the beauty of cumulus and sunshine and sweat, until weeding seemed like a delight people would pay for, (the way people pay to labor and sweat in a gym.)

The poem I was currently struggling with was called “Armor”, and was based on the premise that people become so emotionally hurt, through undergoing traumatic experiences, that they psychologically don protective armor that makes them clank around clumsily in emotional steel, incapable of touching-with and being touched-by love.

The plot involved two old knights who had died in battle. One then reincarnates as a innocent child with no armor. Because the child has a new brain he has amnesia about past pain, but while wandering dreamily in a garden behind his childhood home he finds a doorway in time, and goes through it and meets his old friend, who still has his armor on and is refusing to be born again. The two then get into an argument about whether or not it is worthwhile being born again, and that is where my imagination ground to a halt.

I tried to force myself to finish the poem with sheer willpower, but had “lost the thread”. The plot refused to go the direction I intended. The old knight with armor was a real sourpuss, but he came up with excellent reasons not to be born, while the boy came across as a bit of a twerp, and his logic was lame. I grew frustrated, whereupon the boy in the poem lost his temper and seemed on the verge of putting armor back on and….and…and where the bleep was my poem headed? The poem started to disintegrate into seemingly pointless sidetracks; for example, I might find myself writing about planks made of maple trees, and how the grain of wood changes as the rot sets in.

Frustrated, I crumpled up a page and trudged moodily back up the hill with my orange coffee up. Tubs and Slim were up by the street, leaving, and I could see them regarding me from afar. Tubs was saying something to Slim, nudging him, and Slim was shaking his head sadly. I didn’t imagine they sympathized with the agony of an artist. As they drove off I felt very alone. Inside the house my mother was smoking and pouring over the numbers on her yellow, legal notepad and looking pleased, and, as an aside, without even looking up at me, asked me to drive to the Post Office and pick up the mail. Our postbox was only a half mile away, but I managed to play self-pitiful violins during the drive. Then, in the mail, I saw a light blue airmail letter addressed to me, from India.

I felt a surge of hope. I can’t really say what I was expecting for I wasn’t expecting such a letter. I suppose the simple fact a blue letter had appeared out of the blue suggested I was going to be recognized in some manner. I tore the letter open, and my hope immediately crashed. Indeed I was recognized, but what was recognized was $50.00 I owed.

I was hit by shame. The debt I owed was utterly different from owing a hippy $50.00. Several hippies owed me $50.00, (which was one reason I was flat broke), but I didn’t think it was a big deal. In hippy terms, in 1974, $50.00 was what you made washing dishes for half a week. Minimum wage was $2.00 an hour, (worth roughly $11.00 now, in 2020). But one thing that I had been shocked by in India was the huge disparity in standards-of-living between “them” and “us”.

I became aware being poor in that land meant working for roughly a penny an hour, though there didn’t seem to be a “minimum wage.” Many seemed to subsist on an income so small they could only buy one meal a day. It gave, “Give us this day our daily bread” a far more poignant meaning. However when they sat down for this “bread”, (often a pancake of millet flour called a chapatti, with a gravy made of lentils called “daal”,) they seemed far happier than hippies managed to be, though hippies ate far more.

It is embarrassing to owe money to a person in a “third world nation”. I handed my mother her mail without mentioning my disgrace, and headed back to my shack forgetting to refill my coffee cup. As I slumped by my typewriter my poem “Armor” seemed pointless. It seemed worse than pointless. After all, of what concern are the problems of a couple of imaginary and dead knights named “Siegfried” and “Heinrich”, to the people of India? I had no excuse for failing to repay the money I owed. All the excuses I used, (which other artists had taught me to utilize on Americans), became utterly hollow when I tried to use them on people who suffer under hot sun for a penny an hour. The people of India didn’t need some ridiculous poem. They needed $50.00. And this meant I needed to work a Real Job.

Worst was the fact the repayment was needed immediately. I glanced around the shack for something I could sell, but I really didn’t own much of value besides my car. I had a pile of LP albums, but no record player. Beyond that I had nothing but old clothes, books and papers. In fact, as I looked around, my entire life seemed more or less worthless.

I saw it wouldn’t take Sherlock Holmes to figure out the shack wasn’t inhabited by an illiterate clam-digger, and rather by some sort of intellectual. I always felt a clean desk was the sign of a lazy mind, and had six projects going on concurrently, but now they seemed like six silly ways of avoiding the fact I was doing nothing: The busy-work of a man suffering solitary confinement.

My interest in meteorology was demonstrated by notes of the daily readings of my max-min thermometer, and a graph of these readings as opposed to the average, with the time above-normal carefully shaded red and the time below-normal shaded blue. There were also numerous New York Times weather maps (far better then than they are now) clipped from my stepfather’s discarded papers and taped in chronological order on the wall. But what was the use of an avocation without a vocation?

There were also a few charts clipped from newspapers on the desk showing unemployment was rising to 10% in Maine as the Gross National Product crashed 84 billion dollars in the past year. I had an interest in economics, and had even passed my English university-level “A level exams” in economics (due to two terms frantically cramming under the tutelage of a pleasantly mad teacher in Scotland), but I had no clue how to turn such knowledge from an avocation to a vocation. However it did remind me to turn on my battered, crackling radio to listen to the noontime financial report.

I tried to forget my problems and focus on the news. They called the crashing GNP “stagflation” because prices were soaring even as economic growth slowed. It seemed obvious to me prices would soar, considering the Arab Oil Embargo had doubled the price of oil, but the snooty experts on the radio looked everywhere but at the obvious. One fellow stated that the government’s efforts to “stimulate” the economy made people buy bonds rather than investing in businesses, pointing at the component of GNP called “investment”, which had fallen to barely more than half of what it had been. Another fellow blamed women for getting fed up with being home-makers, and joining the work-force in such droves that it shrank wages and increased unemployment. A third fellow blamed “jittery” investors, because the communists in Vietnam seemed unlikely to abide by the terms of the peace-treaty Nixon and Mao worked at, with Nixon now disgraced and Mao now drooling at death’s door. The only good news was that exports, a minor component of GNP, had shot upwards. This was especially good news for coastal areas like Maine, but I shut the radio off, suddenly struck by the utter worthlessness of contemplating billions of dollars when I couldn’t even come up with fifty. Ordinarily I’d be intrigued by President Ford’s idea that tax-cuts might end the “stagflation”, but of what use are tax cuts when you make no money, and therefore pay no taxes?

My eyes roamed further along the desk to an absurd chart I had devised to better control my moods. It was based on my feeling that modern psychology was pathetic and in need of drastic improvements, and also on the then-popular idea of “biorhythms”. I was attempting to chart my inner weather the same way I charted the weather outside, thinking that, if I knew what my moods would be before they happened, I’d be better able to handle them; I’d be one step ahead; I’d have an umbrella if the forecast was rain. Now it all seemed worthless. You cannot predict the weather with perfect certainty, nor the economy with perfect certainty, nor your moods with perfect certainty, but one thing was perfectly certain: I needed fifty dollars.

I thrashed in irritation, and my eyes next chanced upon five separate volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica and a novel from the local library. My stepfather had noticed the five holes in his bookshelf, and had asked me to return the encyclopedias the night before, and also I could not afford even library fines when flat broke. With a sigh I prepared to gathered the books up and embark upon the journey back up the hill. Hell if I had time to pursue historical research, if I had to get a Real Job, but merely thinking that thought paused me yet again.

I glanced out the window at the harbor, thinking of how my mind always got sidetracked. I had two catagories for this sidetracking in the “mental activity” of my “biorhythms” chart, and I swiftly jotted a 1.25 in the “wondering” column and a .75 in the “wandering” column. Then I laid my hands on the pile of books without picking them up, thinking how my “research” had sprung from a visit Slim and Tubs paid after a prior job.

Both my mother and stepfather loved books, but when they first moved into their new home the inner living room wall only held two garish pictures, and a small table between them with a garish vase. My parents wanted the entire wall turned into floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, and my stepfather wanted a wall of his study made the same. Enter Slim and Tubs. After they were done they dropped by for a small, final payment, which could have been mailed, but they’d rather have coffee in the process of being paid. (Considering how cozy the local diner was, they were flattering my mother greatly by preferring her coffee, though they may have also been on the lookout for future employment).

Outside the landscape had been shuddering under the first arctic blast of winter, and Tubs came in overdressed as Slim entered as if he didn’t notice the cold. Tubs wore a very puffy parka that made him all the rounder, a sheepskin “mad bomber” hat with enormous ear-flaps down to his shoulders, and a gaudy scarf of a crimson plaid. Slim wore a baseball cap, a plaid shirt, and had his hands thrust deep into the pockets of his jeans. Perhaps his plaid shirt was a bit thicker than usual, but my mother exclaimed, “Poor soul! You must be frozen!” Slim smiled, but Tubs teased, “After minus forty on Chosin Reservoir, zero seems like a heat wave, to Slim.” Slim winced and shot Tubs an irritated glance, and my mother looked surprised, and then adopted a sympathetic expression that confused me. I couldn’t read the Greek on their faces. I should have asked some questions, but instead I was shy.

I retreated, and got the “K” encyclopedia to look up “Korean War” and see if I could find a mention of the “Chosin Reservoir”. It would have been far easier to simply ask Slim, as he’d been there, an actual eyewitness, but shyness made me into a parody of Sherlock Holmes, sleuthing when it was unnecessary.

Now such private-detectiving can be done via the internet. If you are too shy to talk to actual humans you can sleuth with the click of a mouse. But back in 1974-1975 I had to run up and down a hill, sleuthing with volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica, and then visit the local library, employing the Dewy Decimal System and card catalogs to discovered an obscure history that likely never sold many copies, with some name I can’t remember, (such as “The Chosin Few”).

What I discovered was a wonderful way to sidetrack; engrossing historical trivia which made it hard to be practical, and easy to forget to put wood in the shack’s stove until I noticed my nose was getting cold. Not that I would have discovered much, within the Encyclopedia Britannica. There were things not mentioned in the “K” volume that I found in the “C” volume, under “Cochin Reservoir”, and things not mentioned in the “C” volume that were mentioned in the three subsequent volumes I browsed, but I always had more questions than answers. The obscure autobiography from the local library was a wealth of information buried midst atrocious writing, but if I wanted better I surely should have interviewed Slim, but I was too shy.

In school the Korean War had been described as a “conflict” and a “stalemate”, which made it sound like nothing had been achieved, and even as if nothing had happened. Midst the drab facts of the encyclopedia I saw drab dots, but I could connect the dots, and saw that, as always, war was hell. Through that hell Slim, as a teenager, once walked.

To me the leaders on both sides appeared to be a bunch of idiots, with the UN particularly moronic in terms of gathering intelligence, and Mao particularly moronic in terms of logistics. For example, the UN forces had marched victoriously from the very south to the very north, and assumed they were “mopping up” the final North Korean troops. They even named a maneuver “Operation Home-By-Christmas.” But in fact they were facing 120,000 Chinese troops. Yet Mao, in his haste to prove Chinese could fight better than Europeans, proved Chinese leaders could be equally stupid as Europeans, (though perhaps not quite as stupid as the English at Verdun), for he sent 120,000 of his finest troops south without food and in summer clothing. The cold swiftly killed more of his best men than the UN forces did.

The plight of the foot soldiers on both sides was extreme. At minus forty nothing worked right. Batteries failed and tanks wouldn’t start and walkies-talkies went dead and diesel fuel turned to jelly and guns jammed. Confusion reined on both sides. (One drab phrase from the encyclopedia seemed especially lacking in compassion to me: “Failed to fortify their positions.” It may have been factual, but failed in its own right to comprehend the desperate extremes both sides faced.)

At one point the starving and freezing Chinese troops overran a UN base, and logically assumed the hugely outnumbered and routed UN troops would be hightailing it south. What they didn’t understand was that the UN didn’t understand. Rather than seeing they had been attacked by a huge army, the UN thought the attack was the deeds of desperate North Koreans near the end of their rope. If the Chinese were noted it was assumed they were only a few “advisers”. Therefore the tiny force counter-attacked the huge force, and found the Chinese had “failed to fortify their positions”. Why not? Because they were doing what men do when at their wits end and on the verge of starving and freezing to death: They were rummaging through captured supplies for warm clothing and food. Many had dropped their guns; and they were as surprised by the counter-attack as the UN forces had been by the initial attack, and the rout became a counter-rout. But this then fostered the illusion among the UN forces that they should continue attacking north, when what they should have done is to use the snatched reprieve to swiftly organize a defended retreat south. In the fog of war they probed north, and they soon again met the might of superior numbers and a counter-counter-attack, and were overrun a second time. Units were encircled and cut off, unable to retreat south, with Chinese troops on all sides, and in one of these trapped units was Slim.

During the day the air was filled with the nearly constant droning, roaring and booming of American airplanes and jets, attacking from a base to the south and five aircraft carriers, but as the sun fell and the cold grew fierce all became quiet, and under the dim glow of flares Slim awaited the inevitable Chinese attacks. The dark had a nightmarish quality; you snatched sleep during the day. The encyclopedia showed neat lines and arrows of red and blue, but the battle was an extended melee, a derangement.

Just days before Slim had been patrolling northward through a landscape much like Maine’s, right down to the scattered wood-frame houses and long stretches of wilderness between towns. He was wary, and scared of snipers, but only heard shots and explosions far away. The weather was brisk and autumnal, and he’d been dreaming of being home by Thanksgiving, when suddenly weather colder than he had ever experienced and Chinese troops came storming down from the north.

A man never knows what he can do until he has to. Slim saw sides of himself he never knew existed: Horror, terror, grief, and the rage of a cornered rat. He saw bravery isn’t what you want to be, but what you have to be. But even more disconcerting was elation and hilarity midst all the horror, brotherhood midst bestiality.

One time Slim spotted two Chinese laying in ambush. He was uphill, but they were looking down as a patrol of Slim’s comrades crossed the slope further down. Slim raised his gun to shoot them, but the gun jammed in the bitter cold, so Slim drew his knife and crept up behind them, his pulse thudding in his ears. Then he realized they were frozen to death. Slim heard his own voice first giggle, then sob a single sob, and then growl to himself in the voice of a sergeant, “Keep moving, Private. Move!”

To bolster courage every other word became “fucking”. “Fucking get fucking ammo fucking fast!”

During hand-to-hand fighting airstrikes dropped napalm, and in he hellish heat some Americans roasted along with the Chinese, and a man cursed, “Fuck if I ever fucking pray to God to make it fucking warmer, ever fucking again”. For some insane reason midst insanity this sarcasm caused Slim’s squad to dissolve briefly in paroxysms of helpless laughter, before they all abruptly regained their grimness.

Surrender didn’t seem to be an option for either side. This went against the history of the Chinese warlords, who had tended to defect whenever it was to their advantage, as squads and even as entire divisions, both when fighting Japan and in their own Civil War. Now they fought to the final man, perhaps because Mao had executed the warlords and all were unified under him, or perhaps because his troops knew if they stopped moving they’d freeze, and prisoners would be forced to stand still. Meanwhile the Americans had seen or heard that Koreans were brutal to prisoners: The South Koreans slaughtered the North Koreans as predictably as the Communists “purged” the Non-Communists. The fighting was do-or-die, with the Chinese determined to bottle up and wipe out the UN forces, and with the UN (largely American) forces desperately attempting to break out and force their way south. Retreat was not a matter of backing up. One American officer famously stated, “We’re not retreating. We’re advancing in a new direction.”

Slim’s unit had been ordered to take a hill overlooking the road south, but it hadn’t gone well and they’d been driven back. Slim squinted south with the highway blocked, doubting he’d ever see home again. His gun didn’t shoot and his commanding officers were dead . Half of his unit was dead or wounded, and it was so cold the medics had to thaw the small tubes of morphine in their mouths before they injected the wounded. Many of the fellows he was with were teenagers like he was, eighteen and nineteen years old. What to do? Plan A hadn’t worked; what was plan B?

In this desperate moment Slim glanced sideways over the Chosin Reservoir. It reminded him of a big lake in Maine, and midst a tidal wave of melancholy and nostalgia he remembered ice fishing, and a little voice in his head wondered, “Is the ice safe for fishing yet?” Then he abruptly shrieked, “That fucking ice has got to be fucking thick. It’s been fucking colder than a fucking witch’s tit for fucking days.”

It’s unclear who gave the orders or whether there was any order at all. It simply seemed smarter to move out over the ice, which could hold even jeeps, and go around the Chinese rather than fighting through them. So that is what was done, with the wounded brought along, some walking wounded and some dragged. As the Chinese froze, laying in ambush along the road, hundreds and hundreds of troops escaped over the ice.

Arriving at a hastily-constructed airbase at the southern end of the reservoir, with more than half of his comrades dead (1450 of 2500) Slim was surprised to find himself one of the few judged “able bodied” (385), and while more than a thousand were helicoptered out he was assigned to hold the base’s perimeter along with cooks pulled from the kitchen and clerks yanked from their typewriters, as the marines retreated south from the other side of the reservoir, and reinforcing marines battled up from the south. Slim got to spend a week in this lovely landscape.

Rather than praise, Slim found his army unit belittled by the marines for retreating in a disorganized manner. Slim vowed to pound the heck out of the first marine he met in a bar, but the bars were far to the south, and first they had to break out of their base and fight south through “Hellfire Valley”. The Chinese three times blew up a bridge on the road south, but the engineers kept replacing it, supplied by “flying boxcars”.

If it were not for the Air Force they would have been overwhelmed, but in the end Slim made it to the port of Hungnam after two weeks of solid fighting, and then spent another two weeks defending the perimeter of that port as an evacuation like Dunkirk proceeded. The civilians had no desire to stay, and as Slim prepared to depart he saw 14,000 Koreans crowd aboard a cargo ship built to accommodate 12 passengers. (SS Meredith Victory) The next day, on Christmas Eve, Slim got to see North Korea astern, with massive fireworks occurring as the engineers blew up the entire port, so Mao couldn’t use it.

And now here I was, a quarter century later, and we were still fighting Mao, now in Vietnam. It had been going on since before I was born, and Slim had been there at the beginning, when Mao chose division over a United Korea.

I sighed and looked out over the mudflats. The tide was low. Even at winter you could smell the dead clams.

Actually, I mused, it had been longer than a quarter century. What year did Mao begin the Autumn Harvest Uprising? 1927? Nearly a half century ago. For nearly fifty years the drooling old man had been unable to make peace with his neighbors. For nearly fifty years he had been incapable of seeing any ideas but his own as worthy of anything but destruction. All traditions were his foe, all cultural variety was his foe, any power but his own was his foe, was “counter revolutionary”, and anyone outside was an “imperialist”. What an arrogant and paranoid madman! And what stopped his cancer from spreading? Shy teenagers like Slim.

If only people would, as John Lennon sang, “give peace a chance!” What a different world it would have been if people had chosen to get along, rather than choosing divorce, rather than choosing fifty years of murdering millions upon millions.

I shook my head and gathered up the books. Who was I to think I could solve the world’s problems? No one would pay a penny for my poetry, and I needed fifty dollars.

My mother shot me a curious look as I stomped into her house with a grim expression and began replacing the encyclopedias on the shelf. I was known for taking things out, and not for putting them away, so she knew something was up. However I was not about to tell her I needed fifty dollars. She’d fret, and I thought I’d rather face Chinese troops at forty below than face my mother’s worry.

As I drove to the library to return the book I pondered the fact that getting a Real Job would be admitting defeat, in terms of writing and being a poet. But Slim had been defeated at Chosin Reservoir, and it wasn’t the end of him, was it? I needed to adjust my attitude, and see my retreat was actually “advancing in a new direction.”