One aspect of watching ice melt is that one becomes aware of misconceptions we all have, and which the media should end but doesn’t. For example, people tend to think certain parts of North America are arctic, when they are not. All one needs to do is trace lines of latitude from North America around to Europe, and one gets their eyebrows lifted. The southern tip of Greenland is at the latitude of Stockholm, Sweden; and the southern end of Hudson Bay is at the latitude of Hamburg, Germany.

If course it spoils the thrill of sensationalism if you mention, showing water pour off a glacier in Greenland, that it is as far south as Stockholm. The public then would compare a picture of flowers blooming in a Swedish summer park with the craggy coast of Greenland, and it would seem less surprising that ice melts at the edge of Greenland’s icecap.

In like manner, when writing about how swiftly the ice breaks up in Hudson Bay, it spoils the element of Alarmism if you mention it is as far south as northern Germany. Rather than the melt seeming surprising it would seem surprising that ice remains in July, for people would think how surprising it would be if there was ice on the sea-coast of Germany in July.

The fact of the matter is that it thaws right up to the North Pole in July, and temperatures can be above freezing and still below normal.

Once you become aware that thaw is the norm up there in July, what becomes more interesting are the places that dip below freezing. It is quite common, for temperatures only need be three degrees below normal, and the rain changes to snow.

One thing I miss very much is the cameras we used to have drifting around up there. As recently as 2014 2015 we had seven views, and could witness fresh falls of snow and brief refreezes of the melt-water pools. These were especially interesting because the satellites tended to miss these events, perhaps because they occurred at the wrong time of day, perhaps because they happened in a very small area, perhaps because refreezes involved a very thin layer of air right at the surface, or perhaps for some other reason. In any case, they stopped funding the cameras. (Let us hope the de-funding was not because certain people didn’t approve that the cameras showed freezing where politicians claimed there was melting.)

The only camera we have this year is a tough one, O-buoy 14, which refused to be crushed by ice, and survived the winter. It is not out in the Arctic Sea, but down in Parry Channel at a latitude of roughly 74° north. I like having it located where it sits, still frozen fast in immobile ice, because it allows us to compare the current situation with the year 1819, when William Parry sailed HMS Helca and Griper in the same waters.

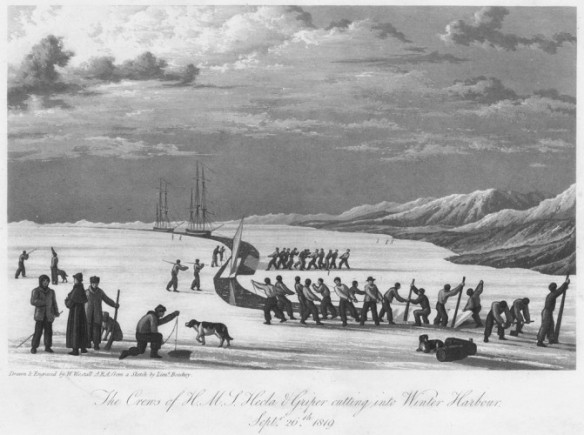

Parry sailed further north and west of where O-buoy 14 now sits, and then, as ice reformed in September, they cut a channel for the two boats, to get close to the shore of Melville Island, where they’d be less exposed to the crushing and grinding of moving ice.

Then they waited for the ice to melt. It was a long, long wait; ten months in all. It is interesting to read how Parry kept his crew from going nuts, especially during the three months of winter darkness. They produced plays and published a newspaper and, as it grew light, conducted expeditions along the coast of Melville Island on foot. Also, when some of the men showed signs of scurvy, Parry planted mustard and cress seeds in his cabin and fed the sprouts to the afflicted men. The first signs of thaw were in March, but the ice remained six feet thick.

In the year 2017 our first signs of thaw were much later, but sudden, and we swiftly developed an impressive melt-water pool on June 29:

Of course, the media would generate sensationalism with such a picture, crowing about how the arctic is melting. Then they would get very quiet when the water drained down through a crack in the ice, as it did by July 8:

The media would get even quieter when the camera then showed signs of fresh snow, as it did on July 12:

And last but not least, there was a cold spell associated with the above view, and the melt-water pools were skimmed with ice, which needed to be melted away to make a little progress on July 13:

What this makes me wonder about is the fortitude of Parry’s crew. They never got moving until August 1. Can you imagine how they felt when it snowed in July? (Or did it snow, back then, when it was supposedly colder?)

Our modern buoy is at roughly 103° west longitude. Parry was able to sail as far west as 113°46’W in the late summer of 1820. Then they noticed ice starting to reform. Apparently no one was eager to spend another winter up there, so they sailed lickity-split east the entire length of Parry Channel, escaping into Baffin Bay and arriving back in England in October.

It will be fun to watch this camera’s view. We are in a race with the year 1820, to see if we can get the ice moving before August 1. (One interesting thing is that, while the Navy satellite suggests the ice in Parry Channel is moving, the GPS attached to O-buoy 14 shows no movement. Once again we see the value of having an on-the-spot witness.)

I actually want the ice to move, so the view shifts around and we can see mountains in the distance.

Stay Tuned!

(Hat tip to Stewart Pid for always keeping me abreast of O-buoy 14 news.)